Faces. Nothing causes me to procrastinate like the task of painting faces. It's not the blank canvas that intimidates me. It's the one with half sketched in figures, ready for fleshing out. The dread of getting started can stall me for hours, days. Painting faces is what I am specifically not doing as I write this blog.

Faces are intimidating almost by design. Anything that can be thought, said or felt is reinforced (or contradicted) by a dense vocabulary of facial expressions. Many great works of art derive their power simply by accurately re-staging these fugitive gestures. The eyes alone are capable of articulating emotions as well as language can do, and most of us are born with the ability to decode those looks intuitively. In explaining the difficulty autistic people have with processing facial expressions, one activist for Autism Awareness describes the pain of looking another person in the eye as equivalent to having his hands held in a fire. No one needs to be told how powerful eye-contact can be. Even animals share this language of looks with us, which is why you can't fake bravery when trying to stare down a mean dog, for instance. They're not just smelling your fear, self-doubt is written all over your face.

For some artists, painting the figure comes considerably easier than for me. The pressure to correctly depict the human face is the most daunting challenge I subject myself to on a regular basis. I need to know I'm at the top of my game before I can even begin to work. This involves being properly caffeinated, which means just enough to feel fully awake, but not enough to make my hand unsteady. I also need to have recently eaten, since there is no worse distraction than hunger. Intoxicants are out of the question as they erode judgement and make hours of re-painting inevitable. Of course the lighting has to be just right, but so does the music (if any), and even the smell of the room is critical, which usually means attending to that damn cat box in the far corner of the basement, and then selecting the right incense. Seasonal considerations apply. Amber is good in the fall, but not lavender. Did I mention tea? I like the herbal kind that claim to focus the mind. I'm guessing those claims are a load of crap, but I'm willing to chance it. If all this sounds a little O.C.D., I'm fine with that. Most of us have our successes propped against some neurosis or other. Mine just happens to be over-preparation of my my work environment, but when I get it right I can disappear completely into the rabbit hole of creative experimentation for whole days without even knowing I've been away.

When an artist draws, paints, or in some other way manipulates materials in attempt to depict something accurately, we call that rendering. To render something is to create a representation of it. Another definition of rendering is to melt down, extract and purify. Rendering is also the word used for the process of breaking down animal carcasses into the components of skin, fat, bone and protein for "reuse." Artists understand how closely related these definitions are. In order to draw something correctly, we first have to break it down into intersecting planes, angles and curves, and then we have to recreate those relationships one by one on a flat, blank surface.

It's no secret that I use a projector to help me rough in my compositions from images I've worked up digitally. I'm fine with people knowing that. My work has about it the sense of accumulated iterations, one of which is digital composition. Many of my source images have had a previous life before I acquired them, and the echo of that prior purpose is what helps give my paintings context. Even the original photography I work from is staged in a way to interact with these appropriated images. A fair amount of improvisation and reworking can happen at any point in the process, with the final painting being just the most recent instance of a palimpsest of ideas. But regardless of the combined-media origins of my paintings, there are still dozens of hours of good old fashioned rendering that go into making my figures "convincing." I may white-out a face two or three times, starting from scratch each time, until I am happy.

But what does it mean to get a face right? Those who study faces quickly learn there is more deviation than norm. Relaying that deviation faithfully is what helps convince the viewer that an image is realistic. Even the most beautiful faces are "out of true" with traditional notions of idealized beauty. There is not a face out there where one eye isn't higher than the other, or the nose slightly bent to one side. Ears are often the least match-y things that make up the human countenance. If you see a face that looks perfectly symmetrical it will somehow look wrong. It's the minute deviations in symmetry that make a face seem believable.

Recently I was painting a face where the nose was a little off center. Just slightly. Something you would never notice in real life about the model I had photographed. I kept trying to center it, but it never looked right. Finally I stopped resisting what was in front of me and put it down as closely to what I was seeing as possible. I remembered a drawing instructor back in college who was watching me in a figure-drawing class. He wasn't looking at what I was drawing, just watching me draw. Finally he said, "you spend too much time drawing and not enough time looking." I'm sure he said that ten thousand times in his career, but it was so perfectly right for me at that moment, and it still is.

Later that day a friend stopped by to chat and I showed him the painting. He said, "Dude, that girl is super hot but she's kind of creeping me out because of the way she's staring." This wasn't exactly what I was going for. It wasn't the whole effect anyway, but it did let me know I'd gotten the nose right. In fairness to my friend, if he had seen the painting on the wall of my gallery he would have put more effort into a context-appropriate response. Still I was happy for the bluntness of it. It helped break that spell you fall under when you're deeply immersed in your work and you're thinking it's doing one thing - usually something heady, but you're missing something much more ordinary.

When I think a painting is done I'll usually post an image of it on my Facebook artist's page just to get some reactions. My favorite thing lately is the way their facial-recognition software kicks in and that little floating box pops up over the faces in my paintings and asks me to tag my "friends." I realize how tawdry it is to allow yourself to be flattered by computers, but I still find it amazing that an accumulation of brush strokes that I put together can be blended in a such a way that even algorithms are tricked into interacting with them. It's a powerful and seductive thing to portray the human form, if even just reasonably well, and it raises questions for me about the moral responsibility of the artist. The context in which the art is received by its public is informed by social values, norms and expectations. Most artists possess some awareness of this dynamic, or at least they pretend to. I'm certain the ethical stakes aren't any higher for figurative artists than abstract or conceptual or what-have-you, but because humans are also animals, we are programmed to respond to representations of our kind in ways that are visceral, not just intellectual. That's what sometimes creeps ME out now that I'm edging further and further into figurative art, but it's also what makes it more fun than I've had in forever.

|

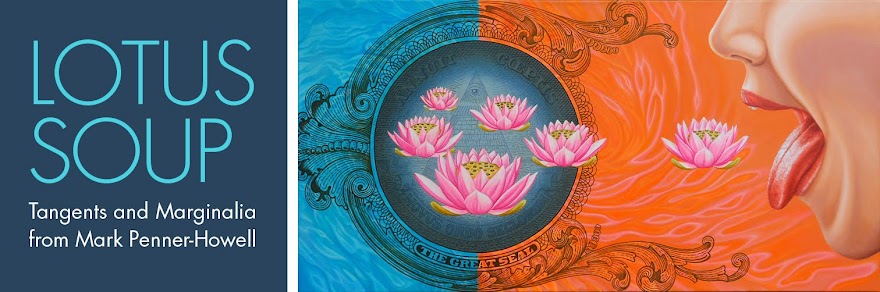

| Semi-Transparent, acrylic on canvas, 2013 |